For roughly two weeks each spring, Japan becomes a stage. Every temple framed, every park rehearsed. The petals fall, the crowds swell, and by May, the magic has already been packed away. That’s if you’re lucky, because if it rains, and it very well might, all those blossoms are on the floor. Gone for another year.

But if you time things right, it’s beautiful, of course, just also exhausting. Like trying to meditate in rush hour.

I used to plan itineraries around sakura season too, as my clients often remarked how expensive travel in Japan can be. Well, yes. If you want to be there when the rest of the world does too, it can get expensive. But what people don’t seem to realise (and it seems very hard to convince them) is that the best season in Japan is the one that comes quietly after it.

The problem with perfection

Hear me out. The Japanese word sakura has become shorthand for Japanese beauty itself. Those pale pink petals appear on perfume bottles, Instagram captions, and airline adverts, promising a moment of stillness that barely exists anymore. The irony is that this most poetic symbol of impermanence has become a global checklist, and a stubborn one at that.

In Japan, the cherry blossom forecast is treated like breaking news. The maps, the charts, the countdowns. By the time the trees bloom, the whole country seems hypnotised. People picnic shoulder to shoulder under trees lit by lanterns, watching petals fall into paper cups of sakura-flavoured convenience-store wine. It’s still lovely, but it isn’t quiet.

And the obsession has gone international. A few years ago, the Japanese and British governments worked together on a vast cherry tree gifting initiative, planting thousands across the UK to turn our parks into mini hanami scenes. It’s a lovely gesture, but it also proves the point: spring isn’t rare, it’s just better noticed. So what else are the Japanese noticing that maybe we miss?

There’s something else about cherry blossom season in Japan. If you go for the blossoms, your fate is sealed: you probably won’t go back.

Cherry blossom tourists rarely do. I think it’s because they believe they’ve “done Japan.” Seen the red gates, the floating petals, the crowds in Kyoto, and they go home thinking that was the country at its best. It’s a beautiful experience, but also an expensive one, and often a little overwhelming. Isn’t Japan supposed to be calm? No. Not in April.

These are the “we’re only going once” people. The checklist travellers. You don’t want to be those people. You want to get it.

The other blossoms

What most people don’t realise is that Japan’s famous week of cherry blossom is only the middle. The season is longer, softer, and in many ways more interesting on either side of it, every bit as beautiful, and far less crowded. Each has its own symbolism in Japanese culture, its own festivals, and its own flavours. Together, they frame spring as something deeper than a photo opportunity: a slow, unfolding story that lasts for months, not days.

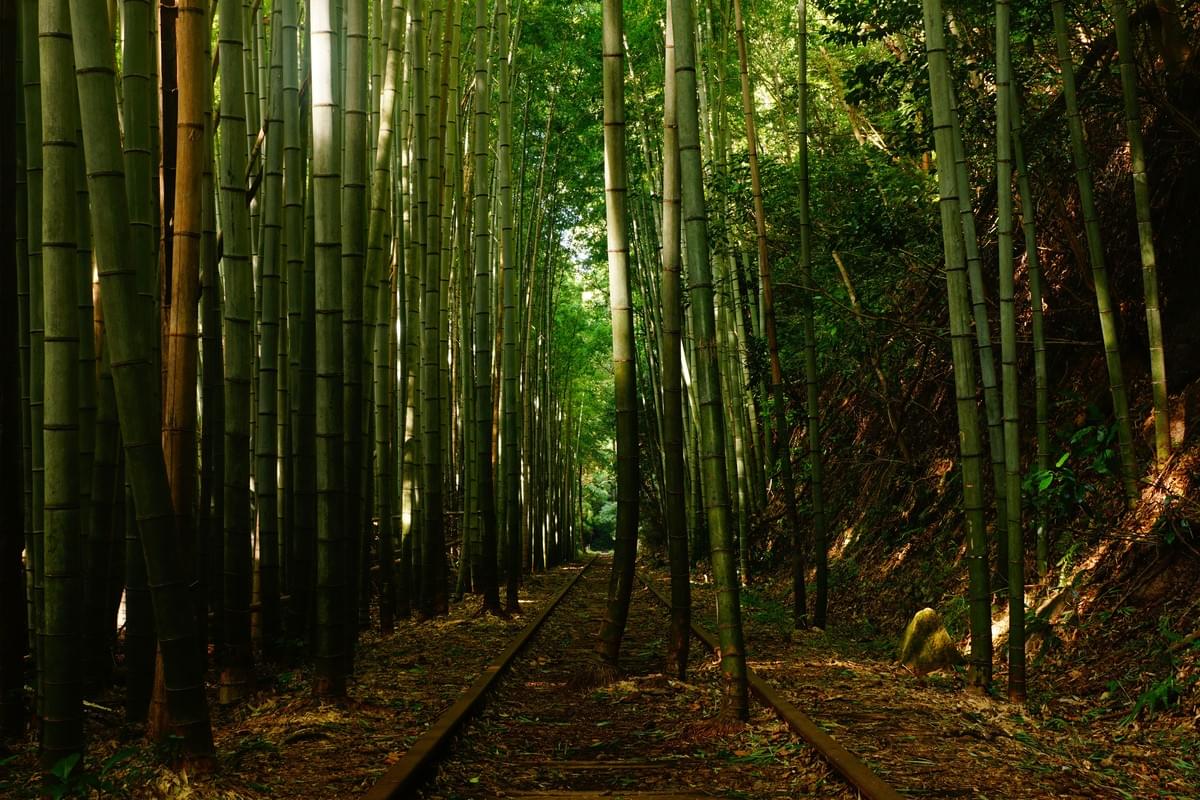

In the old Tenmangu shrines of Kyoto and Fukuoka, plum blossom lingers longer. The trees bloom in early March, smelling faintly of honey and woodsmoke. Locals visit between errands, not in pilgrimage. There are few crowds, no camera queues, just the sound of bamboo sweeping leaves from a courtyard.

By late April, the wisteria tunnels bloom in Tochigi and Kyushu, their lavender petals hanging like scented chandeliers.

Or head to the Shibazakura Festival, where the ground itself bursts into colour, a carpet of pink and white moss phlox stretching towards the mountain.

In May, when the crowds are gone, fields of baby blue eyes bloom along the coast at Hitachi Seaside Park. It’s one of those views that feels impossible to photograph properly. You have to stand in it, wind in your hair, to understand the scale of quiet.

Shinryoku and substance

Then the colour shifts again: The new green arrives.

This is when I tell clients to visit Kyoto’s lesser-known gardens, when the raked gravel shimmers and the air smells of rain. Moss temples like Saihō-ji and Giō-ji feel alive in their stillness, the kind of green that practically glows. In Shimane, the Adachi Museum of Art frames its gardens like paintings. The brushstrokes are leaves, the ink is time.

Skip the sugary sakura snacks and make time for a simple meal of seasonal vegetables and mountain herbs in a local restaurant, the kind where the chef grows his own sansai and the tea tastes faintly of roasted barley. Food as reflection, not performance, and it fits the moment perfectly.

Elsewhere, it’s the start of the tea harvest. In the hills of Uji and Wazuka, women in patterned aprons pick new leaves by hand. You can join them, rolling the leaves over a heated table until the scent deepens from grassy to golden. The first flush of tea is called shincha, literally “new tea”. It tastes like the season starting over again.

This is Japan between moments, where beauty feels unintentional. No peak bloom, no crowd, just a real connection to the season’s rhythm and renewal.

The lesson

The irony of cherry blossom season is that everyone is chasing a metaphor they have already missed. The petals were always meant to fall. The point was never to catch them, but to notice what comes next.

Japan doesn’t need to be timed perfectly. It needs to be felt properly.

Travel after the blossoms and you start to see what locals mean when they say mono no aware, the quiet ache of things passing. You see it in the steam rising from a tea bowl, the sound of carp streamers snapping in the wind, the soft moss in dappled light.

Spring doesn’t end when the petals fall. It renews itself in tea leaves, in moss, in the green shimmer of temples after rain.

If you’re ready to travel with the same calm precision that defines Japan itself, I can show you how.